The one thing you never say to a suicide bomber

Your insistence that I should return to or must operate within your cognitive frameworks — that’s part of what got us here. Your blind spot. What you do not understand.

I picked this joke up sometime during my time in the UAE. Perhaps overheard at the Irish Village (which I happily learned is still going strong). Or who knows. I am sure the joke is quite offensive, so please unsubscribe now with moral outrage.

Here goes:

Question: “What’s the one thing you never say to a suicide bomber?”

Answer: “Don’t do that — you might get hurt.”

I will be the evil terrorist here. If I am strapped up and prepared to blow things and people up, threatening me with harm will likely not be productive. I’ve already made that calculation, and accepted not only the risk but the outcome. You trivializing my commitment only reinforces it. To you, I might understandably appear to be insane and outside the bounds of civilization. But at this moment, you are one out of touch with reality — a reality I am about to shape further by however briefly imposing my will upon it.

Your insistence that I should return to or must operate within your cognitive frameworks — that’s part of what got us here. Your blind spot. What you do not understand. A world which truthfully, even if much of your experience has been otherwise, has no obligation to conform to your desires.

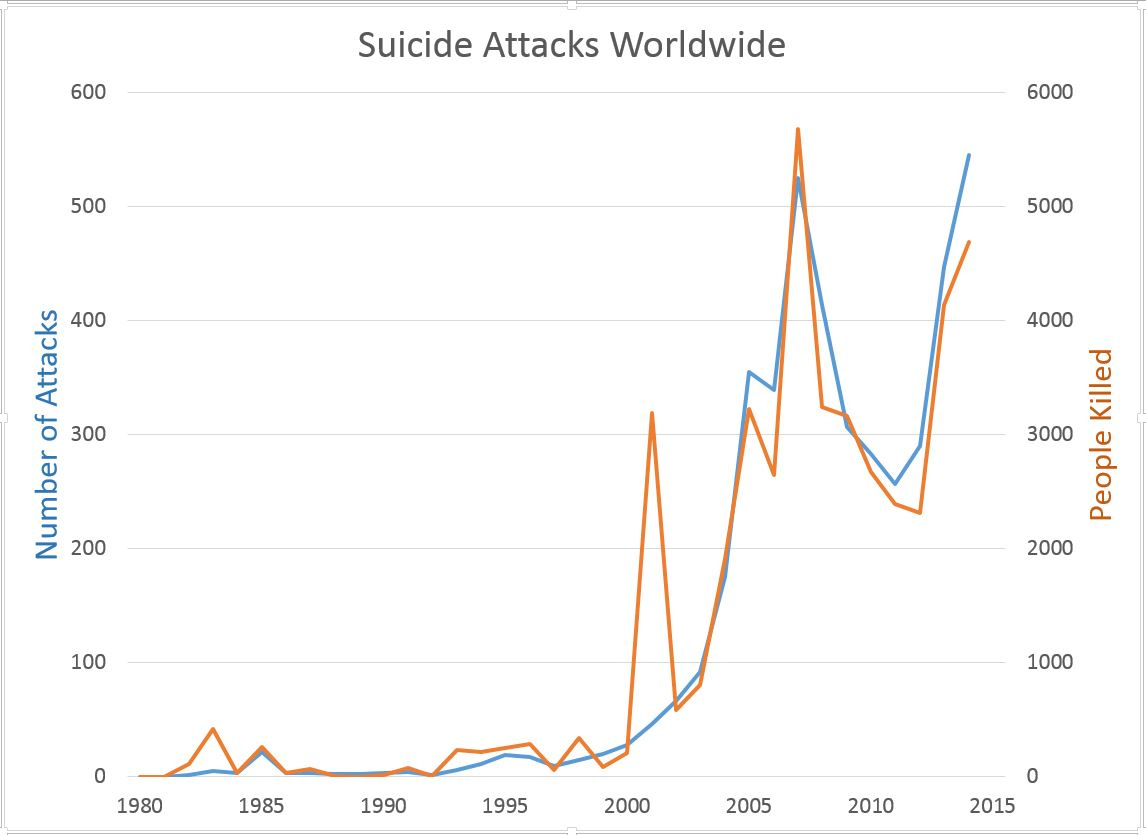

(Graph below by BoogaLouie, CC-BY-SA 4.0. “Results from search of Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism Suicide Attack Database for 1982 to 2014”).

What I am hearing right now in the US mainstream media is pundits and celebrities outdoing themselves to express their moral outrage, to double- and triple-down on the evil that is Putin and Putin’s Russia, and to assure themselves that their sense of how the world should be must prevail.

I understand this psychologically — but it makes for bad decision-making. Let’s go for now with Putin as a thug and insane madman — like our suicide bomber, for example. Putin informed the West that he would not tolerate Ukraine flipping to the NATO. Old news. Professor John J. Mearsheimer pleaded with us to take this seriously in 2014, and in 2015. Keep Ukraine neutral, and work to make it prosperous.

The USA did not, and did not. Instead, we called Putin’s bluff. He was not bluffing. Putin has also threatened to use nuclear weapons if Russia is attacked. The same experts and decision-makers who never thought Putin would invade Ukraine now think Putin would never use nuclear weapons.

Why not? Because he must return to and operate within our frameworks: political, economic, cognitive, and otherwise. Or else what? We will call him a deranged madman, a war criminal, the embodiment of evil, and do our best to destroy him? We’re already doing that — we’ve been doing that.

Sam Faddis, ex-CIA spook

The former CIA case officer Sam Faddis, who with his wife (also ex-CIA) heads up the excellent substack AND, cogently argues that we must Give Putin an Off Ramp. Putin knows the war is not going well. He wants out. But he also needs certain security guarantees: not for himself, for Russia.

Sam Faddis notes of Putin’s demands:

As a starting point for negotiations, frankly, the Russian conditions could hardly be more promising. They boil down largely to a demand that Ukraine recognizes existing borders and stay out of NATO. By agreeing to those terms Ukraine will not, in fact, be giving up anything. It is never going to take back the territories Russia is claiming, and it is never going to join NATO.

So if Putin is losing as the war is proving too costly, and Putin wants to end the war with a treaty, why not keep pressing? Why not destroy this evil man, and this evil regime? Let’s take those questions seriously.

Historically speaking, wars end in three general ways: by annihilation, by attrition, and by agreement.

By Annihilation

The Romans did not conquer the Etruscans: they annihilated the Etruscans, who were replaced by the Romans. Likewise, although Rome did rule over much of the former Carthaginian empire, they annihilated Carthage itself. The Romans kept the former Carthaginian vassal states and colonies, adding to and subsuming them within the Roman empire. But their victory in the Third Punic War affirmed what Cato the Elder had proclaimed: ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.

(Above image: Ruins of Carthage. Public Domain).

We currently understand such wars of annihilation as large scale crimes against humanity. We use labels such as genocide and ethnic cleansing, to start. Despite the rhetoric from Fox News (excepting Tucker Carlson), CNN, MSNBC, and CBS, who really believes that the West should wage a war of annihilation against Russia? And if my fellow Americans do believe this, why do they think that Europe would support such a war? Or Asia? Or South America? Or any nations we desire further commerce and cooperation with?

By Attrition

Some wars seem to go on forever. The Angolan Civil War (1975-2002) went on — with some interludes — for 27 years. It proved devastating to the nation, but ended with ceasefire between UNITA and MLPA after Jonas Savimbi died from battle wounds at the ripe old age of 67 — roughly 20 years higher than average Angolan life expectancy in 2002 of 47.57 years. The US war in Afghanistan (2001-2001) lasted 20 years. In both cases, the wars did not end by decisive military victory.

In Angola, the ceasefire gave way to an election and a flow of petrodollars. Savimbi’s UNITA is still around, and took 51 out of 220 seats in the 2017 parliamentary election; MLPA, took 150; other parties, the remaining 19. The USA was not conquered by the Taliban; and in fact, the US military won all its major tactical encounters in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, on 30 August 2021, the USA conducted one of the most shameful and mismanaged withdrawals in world history. Defeated.

Wars of attrition are particularly awful, but generally end with some form of treaty or agreement.

If my fellow Americans want to fight a war of attrition with Russia using Ukraine as proxy and involving the other nations of Europe, I can assure you that all of Europe is not on board.

By Agreement

Unlike wars that end by annihilation, wars that end by attrition typically have some form of treaty to mark what becomes the end of open hostilities — the end of active combat. So we could include wars that end by attrition in the general category of wars that end by agreement. But they are not quite the same — particularly in their effects on the civilian populations.

The War of 1812 between the USA and Great Britain ended by agreement, despite the British having burned Washington, DC. The Americans and British had agreed to peace terms in the December 1814 Treaty of Ghent, which established the status quo ante bellum (“the situation as it existed before the war”).

In the pre-telegraph era, the international news had to travel by ship and horse. So Andrew Jackson’s dramatic defense of New Orleans in early 1815 was vital domestically, but irrelevant diplomatically. After a mutual testing of strength, the USA renounced any ambitions against then British Canada. Great Britain stopped impressing American sailors and harassing American merchant ships, and resumed as the USA’s largest trading partner. The “Special Relationship” was about to get started.

Three Stark Choices

So we have three stark choices for the Russian-Ukraine war. A war that ends by annihilation. A war that ends by attrition — and eventually, an agreement. Or, a war that ends by agreement, sooner rather than later (which would be a war by attrition).

Sam Faddis thinks it is in the best interests of Ukraine, Europe more generally, Russia, and even the USA, if the war ends sooner rather than later and by agreement. I think Sam Faddis shows great wisdom on this matter.

But judging from the MSM rhetoric, many of my fellow Americans would not agree. Keep pushing and pushing Putin — keep hating on Russia. Etc.

I’ve covered elsewhere how the past few decades have not been good for Russia. The USA has taken some pride in making that so.

Time to invoke George Orwell, but perhaps in an unexpected context. His 1940 review of Mein Kampf. Orwell calls attention to the emotional appeal of “Better an end with horror than a horror without end.”

The American plan for Russia is what — “a horror without end?” If Putin and Russia already have everything to lose — and are losing, what do they have to gain?

No hope, and nothing to gain? We are almost back to the deeply offensive joke to which I began this essay: “don’t do that — you might get hurt.”

On certain points, Putin has been consistent. Remarkably so. In his mind, he is defending Russia. He also has a commitment to the ethnic Russians in Ukraine. The ethnic Russians who do live in a part of Ukraine that would still be Russia expect for Nikita Khrushchev, who never anticipating the fall of the Soviet Union, was playing his own game of keeping Ukraine divided and hence in check. (Below: “Map of ethnic groups in the former Soviet Union.” ZeppelinXanadu2112, CC BY-SA 3.0).

So let’s consider the possibility that Putin does want to defend Russia, and does not want to see it destroyed on his watch. Threatening him and Russia with a horror without end might not prove as effective as many of my fellow Americans think so. If Putin is damned if he does and damned if he does not, then why not share some of that damnation with us?

As Sam Faddis has suggested, Putin would likely settle for something very similar to a status quo ante bellum. The European nations, not the USA, could guarantee Russian security and the end to NATO enlargement — provided that Putin steps down. This would not be the vindictive moral victory which so many American pundits and celebrities crave — but it would prove far better than a war which ends by annihilation, or a war which ends by attrition.

If we agree that the West is cutting a deal — that the Russian-Ukraine war will likely end by agreement, then all other things being equal, the sooner the war ends the better.