Why does Putin still have support in Russia?

Read about what the MSM does not report. Some history and data on why Putin endures, and why foreign-imposed regime change is not the answer.

Vladimir Putin spends every day, every hour of the day, in the vicinity of or surrounded by armed and dangerous men and women. Few of whom lack ambition. Putin is also — if you can trust Western media sources — an incarnation of evil, an international pariah, and a war criminal awaiting trial.

But despite the obvious rewards from the West to anyone who would do so, why has Putin not yet (as of 28 August 2023) been deposed or assassinated? In no small part, Putin has endured because he retains both a strong and broad base of support in Russia — support among the population and key elites.

To understand this, we need to know both how Putin came to power and what he has accomplished for Russia since coming to power.

Easier to work backwards, in this case. Yes, we will cover the details of how the USA helped sway the 1996 Russian election to keep Boris Yeltsin as a puppet in power. Yeltsin, as the evidence will show and as our leaders knew well, was corrupt, deeply dysfunctional, and displayed the instincts of a tyrant.

Likewise, we will also cover at least in passing the globalist rape of Russian assets (including Intellectual Property) under the shock therapy of neoliberal “capitalism” — a kleptocratic lawfare which was anything but free and fair open market competition.

The Yeltsin Catastrophe

But for now, please understand that in December 1999, Yeltsin (and family members) retired wealthy and protected even as Russia itself had plunged into economic and social catastrophe. The word “catastrophe” not used lightly here.

How bad was it?

Stephen F. Cohen, late Professor of Politics at Princeton University and also Professor of Russian and Slavic Studies at New York University, has summarized the situation well:

Viewed in human terms, when Putin came to power in 2000, some 75 percent of Russians were living in poverty. Most had lost even modest legacies of the Soviet era—their life savings; medical and other social benefits; real wages; pensions; occupations; and for men life expectancy, which had fallen well below the age of 60. (2018).

Roughly 75% below the poverty line, the former social safety nets either gone or seemingly broken beyond repair, and life expectancy tanking. Let’s add some more data, and fill out Cohen’s summary with some visualizations.

All data used for the following four graphs is initially sourced from the prestigious Gapminder Foundation, which itself aggregates data from various institutions including the World Bank, the Penn World Table (UC Davis & University of Groningen), et cetera. As per American Exile practice, we provide a direct link to a GitHub repository which contains both our code and data: complete transparency, reproducible results.

Economic Status: GDP Per Capita

The following visualization concerns GDP per capita — or gross domestic production per person. GDP per capita is a standard measure of national wealth and economic power. But we do not want to compare apples to oranges given the actual cost of living may differ significantly per nation, and the purchasing value of a dollar changes over time. So for this data set, the data are in constant 2010 US dollars and inflation-adjusted.

Please recall Yeltsin takes office mid-1991 with the deterioration of the Russia economy well underway. (More on this later). Yeltsin leaves office in December 1999, handing over the Presidency to Putin. Excepting an eight-year foray as Prime Minister from May 2000 to May 2008, in which Dmitry Medvedev assumed the Presidency — with most observers holding that Putin remained the power behind the scenes, Putin has served as President of Russia from 2000 to 2008, and 2012 to present.

As the above graph shows, under Putin’s leadership, the Russia economy undergoes a significant and positive reversal of fortune.

If Constant 2010 US dollars seem not the best benchmark, we can use International dollars based upon PPP: purchasing power parity. In other words, how much does that money — whatever the actual currency might be — buy in the way of goods and services in that country?

Economic Status: GNI Per Capita

The next data set and visualization examine GNI (gross national income) converted to international dollars using PPP. As Gapminder explains: “an international dollar has the same purchasing power over GNI as a U.S. dollar has in the United States.”

Using international dollars based on PPP, the positive economic changes under Putin’s leadership are even more dramatic. Do please note that our ultimate source for both sets used above is the World Bank, a Bretton Woods institution which many international observers have claimed serves American imperialism. If we were to expect a data source bias, surely it would be anti-Putin.

For the economic visualizations above, we are using established data sets with the observations based on known and standardized reporting metrics. Even as we shift among metrics, the general trend emerges as undeniable: under Putin’s leadership, the Russian economy undergoes a significant and positive reversal of fortune.

But, corruption …

Moreover, and contrary to what is constantly reported in the Western MSM, under Putin’s leadership the Russian economy has become less corrupt than before — and certainly less corrupt than it was under Yeltsin’s leadership. (More on Yeltsin’s antics later). How less corrupt — and how do we know this? Once again, we turn to the World Bank, which annually offered a global “Doing Business” rating of 190 nations. Rank order: 1, top; 190, bottom.

In 2010, Russia ranked 124 out of 190. In the most recent 2020 rating, Russia improved to position 28 out of 190. Again, this is from the World Bank – not QAnon.

Public Health and Social Stability

As economic conditions in Russia have improved, social conditions for the majority of Russians have likewise improved. We can examine two standard benchmarks of both public health and social stability: Life Expectancy and Child Mortality. In order to significantly improve either or both, a nation must be getting a number of things right.

Life Expectancy

Under Yeltsin, life expectancy surged downward, recovered somewhat, then starting surging downward again. Under Putin, life expectancy stabilized from 2000 to 2005, and then began surging upward until the recent pandemic — after which it promptly recovered.

To reverse the downward trend in life expectancy, Russia needed improvements in policy, infrastructure, health services, and health care access and affordability. None of these in isolation typically have an immediate effect — people who are already moribund may likely not benefit. But all of these in combination can slow the negative trend, stabilize it, and set the conditions for a rebound — for an upward surge in life expectancy. Putin’s team clearly knew what they were doing.

Child Mortality

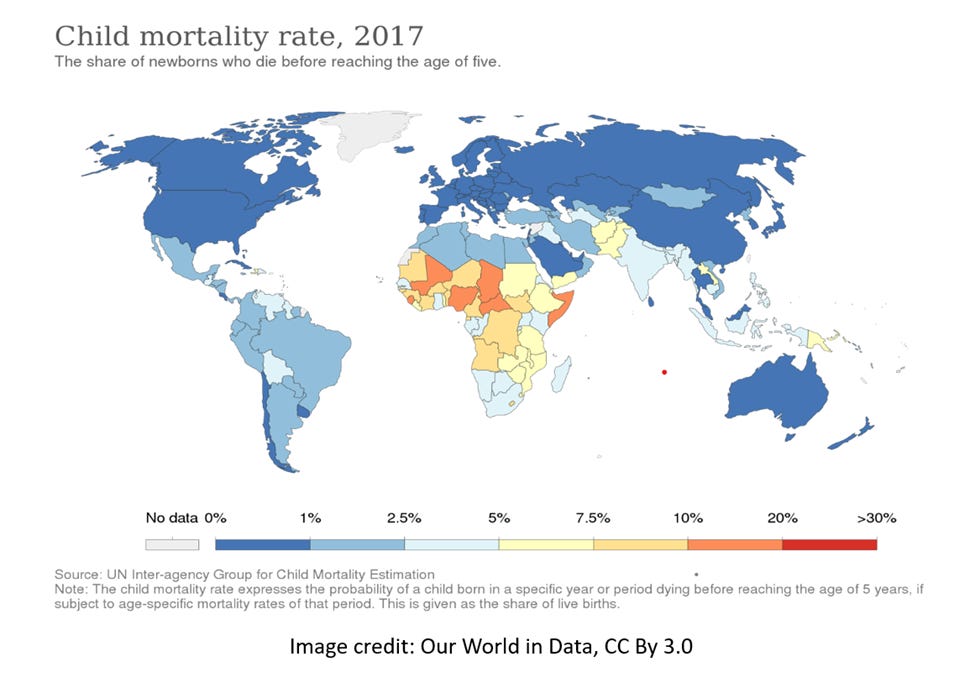

Similar to increasing Life Expectancy, progress on reducing Child Mortality requires success in multiple domains from policy and infrastructure to clinical practices and household environments. The choropleth (stat map) below shows the global situation circa 2017 — and shows that Russia is roughly on par with the EU and the USA. The rate being expressed in percentages is a bit misleading, however: more properly, the “child mortality rate (also under-five mortality rate) refers to the probability of dying between birth and exactly five years of age expressed per 1,000 live births.”

The situation was VERY different when Putin took office in 2000. Russia had a child mortality rate more similar to that of nations in Sub-Saharan Africa rather than those in Western Europe. The visualization below reports on child mortality under age 5, with the numbers indicating deaths per 1000; the data set sourced from the Gapminder Foundation.

In the drastic reduction of child mortality, we have once again compelling evidence that Putin has been serving the Russian people as an effective leader — arguably, at least up until his invasion of Ukraine. That matter for another series of posts.

The four above graphs supplied by Data Humanist help tell the story earlier sketched by Professor Cohen: under Putin’s leadership, life in Russia has improved for the vast majority of people.

The Putin Revival

We discussed earlier the Yeltsin Catastrophe — the general situation in Russia under Yeltsin’s leadership from 1991 to 1999, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Your author also cited Stephen Cohen’s excellent summary of the same.

Before diving into how the USA contributed deeply to the Yeltsin Catastrophe, and pathed the way for Putin, let’s return to Cohen (2018) for a summary of Putin’s accomplishments during the first decade of the 21st century:

In only a few years, the “kleptocrat” Putin had mobilized enough wealth to undo and reverse those human catastrophes and put billions of dollars in rainy-day funds that buffered the nation in different hard times ahead. We judge this historic achievement as we might, but it is why many Russians still call Putin “Vladimir the Savior.”

Based upon credible data concerning key economic and public health indicators, there seems no question that Russia has benefitted significantly from Putin’s leadership and the team he put in place. We find empirical support for — real-world results backing up — Cohen’s 2018 claim that “many Russians still call Putin ‘Vladimir the Savior’.”

Finally, in terms of human rights under Putin because we cannot measure progress purely in terms of economic or public health success, Cohen (2018) has astutely argued the following:

In today’s Russia, apart from varying political liberties, most citizens are freer to live, study, work, write, speak, and travel than they have ever been. (When vocational demonizers like David Kramer allege an “appalling human rights situation in Putin’s Russia,” they should be asked: compared to when in Russian history, or elsewhere in the world today?)

More freedom in Russia or in Saudi Arabia? In Russia, or in China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region? In Russia, or in Australia under the Covid lockdowns? Et cetera, and so on.

Still the consensus remains that Putin must go — a Russian regime change is needed. A brief history lesson in how well this worked the last time.

Choosing Russia’s Leader

Why not replace Putin with a more Western-friendly Russian leader? Regime change, covertly or overtly. And given the presumed benefits of being on good terms with the USA, why would the Russian people not go for this?

The short answer: it’s been tried before. The USA helped rig the 1996 election in Russia to keep Boris Yeltsin in power. We got our man. Details to follow. Russia got a catastrophe — some details above, some more to follow.

The longer answer: for a while, the USA did have an excellent cooperative relationship with Putin on reducing WMD proliferation, and on combatting international terrorism. We trashed that — not Putin. But let’s get back to our previously successful attempt at regime change in Russia — in getting and keeping our man in power. The same man, Boris Yeltsin, who chose Vladimir Putin as his successor.

Our man in Moscow, Boris Yeltsin

In the West, Yeltsin seems remembered if at all as a bumbling good-natured populist who briefly brought democracy to Russia — only be to undermined from within, of course. A Bill Clintonesque figure with a drinking problem, minus a Hillary to keep him on the straight and narrow. We might assess how committed to democracy (and related reforms) Yeltsin was by simply checking the history.

Yeltsin, Democratic Reformer?

As President of Russia, a position he assumed in 1991, Yeltsin sought vigorously to expand his powers and more generally those of the executive branch. This power-push and the rapidly deteriorating Russian economy bought Yeltsin in increasing conflict with the legislative branch of the Russian government, the elected members of the Parliament.

Conflicts of interest and views between the executive and legislative branches of government are generic. In the Western tradition, we know this as “checks and balances” — a government without such checks and balances we would deem well on the way to authoritarianism.

How did Yeltsin our presumed democratic reformer respond to Parliament’s push-back? He dissolved Parliament by decree and by force. Yeltsin ordered tanks to fire on the Russian White House (the equivalent of the US Capitol Building), sent in paratroopers, and performed what some political scientists deemed a “self-coup.” He would rule by decree, not by consent — supported by the oligarchs and the West, not by the Russian people.

The response by our White House? The equivalent of “Yeltsin, you naughty boy. Well done!” As we learned 25 years later. Please consult the George Washington University National Security Archive (Oct 4, 2018) documents and discussion for more details: “Yeltsin Shelled Russian Parliament 25 Years Ago, U.S. Praised ‘Superb Handling’.” One can only imagine Bill Clinton’s envy of his Russian counterpart.

Truth and Sanity when Convenient

Even the Wall Street Journal, albeit again 25 years later, took notice in an op-ed by David Satter, “When Russian Democracy Died” (Sept 20, 2018):

Dramatically violating the constitution he swore to uphold, President Boris Yeltsin signed a decree abolishing the Russian Parliament, the Supreme Soviet, on Sept. 21, 1993. That set the stage for a two-day civil war in October, which cost at least 123 lives, and led to the rise of a dictatorship. By December a new constitution had come into force creating a super presidency and a pocket Parliament, the State Duma, which does not have the ability to contest executive power.

Credit to Satter for getting the easy call right — by abolishing and then attacking Parliament in order to rule by decree, Yeltsin was NOT engaged in democracy promotion. Evidently, in 2018, the Overton window was briefly open in the USA to selectively discuss the fiasco we aided and abetted.

A decade earlier but well into the Putin era, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty in 2008 published an op-ed by a member of that Parliament, Ruslan Khasbulatov, who both witnessed the attack and was arrested shortly thereafter. In “Yeltsin Destroyed Parliamentary Democracy In Russia,” Khasbulatov (Sept 29, 2008) identified (at least) three major consequences:

Yeltsin “concentrated unlimited dictatorial powers in his own hands” as he “imposed on the country a constitution that does not even provide any longer for a parliament.”

In this new Russian Federation under his sham constitution, Yeltsin was thus left unhindered to conduct the "endless Chechen wars, Caucasian wars" which resulted in "a society with militaristic tendencies, a society rent by enmity, a society in which people distrust each other.”

And this “war psychology” in turn “has left an indelible mark on the individual and collective consciousness; it is the source of mutual ill-will and the massive increase in corruption.”

Perhaps you think Khasbulatov (Sept 29, 2008) has exaggerated, a woulda coulda shoulda lament, but there is more. We come now to operation re-elect Yeltsin, our naughty boy, our big man in Moscow.

Fixing the Russian Election of 1996

The pesky democracy thing did not go away entirely — both because the USA needed to justify further interventions and because appearances needed to kept up. Yeltsin, now deeply unpopular, was up for re-election in 1996. (For causes behind Yeltsin’s unpopularity, please recall the earlier data visualizations about the condition of Russia under his leadership).

The Clinton administration and permanent Washington (since “deep state” is now a conspiracy term) were determined that Yeltsin should win.

Mary Elise Sarotte, the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Distinguished Professor of Historical Studies at John Hopkins University, has worked the archives, did the interviews, and established a major chunk of the historical record in her masterwork Not One Inch More: America, Russia, and the Making of a Post-Coldwar Stalemate (Yale UP, 2021).

Big Money, Grift One

Yeltsin needed money for his campaign. Big money. He could not count on contributions by the majority of Russians then living below the poverty line. But he could count on the corrupt oligarchs, and he could count on the West. Let’s start inside Russia, first. As Sarotte (2021) has summarized:

A small tier of oligarchs had enriched themselves impressively while the average Russian was struggling with unemployment, poverty, and pensions of vanishing value. In the course of 1995, it became clear to Talbott [USA Deputy Secretary of State] that Yeltsin had engaged in a series of Faustian bargains with those oligarchs. In exchange for siphoning their wealth into the Russian president’s “campaign war chest,” [Talbott wrote in a 1995 memo] the Kremlin “paid the oligarchs back with vast opportunities for insider trading,” including the infamous loans-for-shares deal, which was essentially a corrupt auction of state assets.

As an in-text footnote by your author, during Yeltsin’s rule, the insider trading was extended to select Western players. This ransacking and pillaging included Russian IP, intellectual property developed at various universities and institutions. Your author in the 1990s knew some graduate students from a fairly prestigious USA program in Russian Studies. A couple of them — employed as translators or cultural experts — got jobs during the Yeltsin gold rush, working in Russia for Western law firms or private equity firms. When later socializing with their old grad school cohorts, these adventurers shared stories about their dubious participation in legalized looting of Russian properties, intellectual and tangible. Fire sale!

Spinning Boris

But the oligarch money was not enough — the polling still showed Yeltsin headed into trouble. The Clinton administration, as Cohen (2018) has explained, “arranged for American election operatives to encamp in Moscow to help manage his [Yeltsin’s] campaign.”

Interference in a foreign election? Well, as Cohen (2018) again has recorded:

So large was the role of the American “advisers” in Yeltsin’s (purported) victory that Time magazine bannered it, “Yanks to The Rescue,” on its July 15, 1996 cover and ShowTime made a feature film, “Spinning Boris,” about their heroic exploits as late as 2003. No one asked, as we should, whether any Americans should be so intimately involved in any foreign elections.

All this does — or should — add comedic context to vastly overblown claims of “Russiagate”: the alleged Russian interference in the 2016 American presidential election.

But “Spinning Boris” was not enough either. More money was needed. Bigger money.

Big Money, Grift Two

Bill Clinton to the rescue. Once upon a time, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had begged the USA for millions in loan money to help further his truly democratic reforms and to help stabilize the Soviet economy. No American presidents stepped up with the big bucks to rescue Gorbachev. But to keep Yeltsin in power despite his known abuses and corruption, Clinton started by putting the screws to that other Bretton Woods institution, the IMF, for a three-year $10 billion loan. Without the usual IMF accountability strings attached, to the dismay of many IMF staffers. At the time, as Sarotte (2021) has noted, this loan was understood by many as discrediting the stated mission of the IMF.

Once the ball got rolling, the World Bank and Japan chipped in — bringing the loan-packages / campaign contributions to roughly $22.6 billion. Real money even today —and more so in the mid-1990s. Yeltsin freely splashed the cash in hopes of getting re-elected. Yet as Sarotte (2021) has cogently observed:

Whatever the exact amount, it did little good. Since the IMF funding was not accompanied by sufficiently credible fiscal measures, the funds quickly floated out of Russia.

Oops. Not necessarily out of the hands of the Russian oligarchs and their Western enablers, but out of the beleaguered nation. With so little accomplished on the ground, Yeltsin was still in trouble come election time. Except that the USA would not let him lose: see no, hear no, speak no evil.

Widespread Voter Fraud Witnessed

The fall of the Soviet Union followed by the comedically tragic dysfunctional government of Yeltsin resulted in hardships for the people of Chechnya, then (and now again) a republic within Russia. To simplify a complex history, the Russian citizens of the Chechen Republic gave up on reforms and sought independence instead. We must add that the Chechen peoples are generally ethnically and culturally distinguishable from Slavic Russians, and Islam is the dominant religion in the republic.

Although the Chechens initially succeeded with their independence movement and did establish a de facto state, the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, Yeltsin responded with a brutal, multi-year crackdown. Our concern here is the First Chechen War, from December 1994 to August 1996, as it impacted the election in a strange and wonderous way. The brief summary below derived largely from Sarotte (2021).

The First Chechen War resulted in a crisis of Chechen refugees (people who fled Russia entirely) and IDPs (internally displaced persons). When election time rolled around, international observers estimated that fewer than 500 thousand (1/2 million) adults remained in Chechnya.

Your turn. Please estimate the number of Chechens who voted in the 1996 Russian presidential election.

Now, please estimate the number of Chechen votes counted by Russian election officials. If for this second estimate, you guessed over 1 million votes, you are correct!

Now, please guess which candidate received about 70% of these 1 million plus Chechen votes. Boris Yeltsin, the incumbent, who was waging war against Chechnya? Or his opposition?

The correct answer is “Yeltsin.” The Democratic reformer. Below, selected scenes from his “get-out-the-vote” campaign.

As Sarotte (2021) has reported:

Later, a member of the OSCE election-observation team claimed that he was pressured not to reveal the “widespread voter fraud” he had witnessed. A US diplomat serving in the Moscow embassy at the time of the election, Thomas Graham, asserted that the Clinton administration knew the election was not truly fair, but it was a case of “the ends justifying the means.”

The election was neither free nor fair, and was subjected to massive foreign interference. But permanent Washington, the Clinton administration, and most of our Foreign Policy intelligentsia celebrated both the tactics and the outcome because we got our man in Moscow re-elected.

Democratic Election or Foreign-Imposed Regime Change?

A strong case can be made that the 1996 Russian election was not democracy in action but USA-sponsored regime change. Yeltsin’s second self-coup — with help from his Western friends. (American Exile will have an upcoming post on the problems with foreign-imposed regime change).

Let’s wrap this one up. The USA helped put Yeltsin back in power. But the destruction of Russia as a nation became so widespread that Yeltsin had to go: the Russian people hated him (and many still do), and he was even losing support of the oligarchs because of the chaos under his leadership.

Yeltsin and his circle — including various family members — wanted a safe exit while keeping their (now) vast wealth. The Russian decision-makers behind Yeltsin needed a fixer, not just a hammer, but someone who could actually get things done.

Blowback: “unintended harmful consequences; unwanted side-effects”

Putin had proven himself as someone who could play ball, work with the system, and still deliver results — but he was also a Russian patriot. During his time in Cold War Germany, Putin had numerous opportunities to defect to the West; later, to emigrate from Russia, or to go into private business, etc. Neither a simple opportunist nor a generic apparatchik, and deeply knowledgeable about the West from his KGB career, Putin remained in public service and navigated the chaos of the Soviet Union collapsing.

Yeltsin appointed Putin as his successor: to finish out Yeltsin's term, to grant Yeltsin immunity, to and clean up some of the mess. The rest, as they say, is history. When the next election rolled around, Putin won. He has remained in power since — including the Medvedev pseudo-interregnum of 2000-2008.

We should not expect the Russian citizens to rush to embrace an American solution to what we perceive as their leadership problems. They tried that — or rather, had it imposed upon them. It led to the near-destruction of Russia as a nation. Moreover, since the destruction of Russia too often seems the declared goal of many American politicians and pundits, even if more as rhetorical flourish than articulated policy, we should not expect Russia to cooperate on our terms with their own demise.

The blowback from operation re-elect Yeltsin (aka, “Spinning Boris”) was Vladimir Putin. If the USA has another catastrophic success with a regime change that displaces Putin, God only knows what the blowback from that will be. But likely nuclear and biological, to start. Putin will not live forever. Let the peoples (ethnically, linguistically, culturally diverse) of Russia determine Putin’s successor.

Your piece made me recall stories I heard from some of those private equity firm types who told me of the first cons on the Russian people made by the oligarchs and foreign investors. Involved the privatization of publicly held businesses, like utilities, energy, manufacturing, all industries all previously owned by the Soviet State.

Every Russian citizen was given shares of stock in them as they were apportioned. Russians, uneducated on western financial instruments, private capital about the value of stock shares received their shares but had little appreciation for the inherent value in the stocks. And while they would be queuing up for bread lines or other lines waiting to purchase goods or register for other means of subsistence would be approached in line by people offering to buy their shares for tiny fractions of what they were worth. Hungry and oblivious, many Russians would take a few rubles for the stocks worth thousands. Happy to have received "free" bread that night.

Meanwhile the people who bought the shares were working for the oligarchs and foreign investors, receiving a few rubles for the shares they purchased with the money they were previously given. Allowing the oligarchs and foreign investors to round up vast wealth in stock holdings of those formally public companies that were privatized and allotted to ordinary Russian citizens.

Those types of corruption and predatory practices was commonplace. And fortunes were made. And turned the Russian people against the idea of capitalism, their only experience being getting ripped off by the wealthy greedy - just like they always had been told in the USSR. Yes. Putin endures. And the west isn't trusted. For damn good reason.

Very interesting,DH: you got at least one reader waiting for the next episode in the serial.

Ugh. Just wading through the memories of the snake pit of the Clintons and Boris: smarmy, dangerous & deadly.

Don’t watch TV since ‘Brought to you by Pfizer’, but subscribe to Vanessa Beeley, still living in and reporting from Syria. Currently reading “Operation Aleppo - Putin’s Military Intervention in the Syrian War”, from 2015, yet deja vu.

Why is it that whenever I hear/read Putin, or Russian spokespeople, or simply their citizens, they sound like grownups?